- Home

- Harry Browne

The Frontman

The Frontman Read online

About the Author

HARRY BROWNE is a lecturer in the School of Creative Arts and Media at Dublin Institute of Technology. His journalism has appeared in CounterPunch, the Dublin Review and many Irish newspapers. Born in Italy and raised in the United States, he has lived in Ireland since the mid-1980s. His previous book is Hammered by the Irish: How the Pitstop Ploughshares Disabled a US War-Plane – With Ireland’s Blessing.

COUNTERBLASTS is a series of short, polemical titles that aims to revive a tradition inaugurated by Puritan and Leveller pamphleteers in the seventeenth century, when, in the words of one of their number, Gerard Winstanley, the old world was ‘running up like parchment in the fire’. From 1640 to 1663, a leading bookseller and publisher, George Thomason, recorded that his collection alone contained over twenty thousand pamphlets. Such polemics reappeared both before and during the French, Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions of the last century.

In a period where politicians, media barons and their ideological hirelings rarely challenge the basis of existing society, it is time to revive the tradition. Verso’s Counterblasts will challenge the apologists of Empire and Capital.

The Frontman:

Bono (In the Name of Power)

Harry Browne

CONTENTS

About the Author

Introduction: ‘This is not a rebel song’

1 Ireland

‘What a thrill for four Irish boys from the northside of Dublin…’

Dandelion Market

War

Self Aid

Mother

Peace of the Action

Where the Cheats Have No Shame

Mr Bono

Property Baron

After the Deluge

2 Africa

Do They Know It’s Christmas?

Bad

Into Ethiopia

‘I’m not a cheap date’

Hearing AIDS

Making History

Seeing (RED)

Editorial Control

More Baggage

Another Edun

3 The World

Beautiful Day

Wealth

Elevation

Zoorophilia

The Spiritual American

More War

Dreaming with Obama

Cui bono?

Grassroots

With or Without You

Acknowledgements

Notes

Copyright

INTRODUCTION: ‘THIS IS NOT A REBEL SONG’

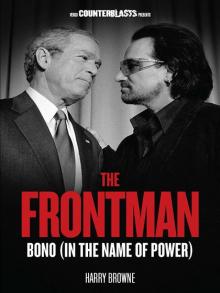

Celebrity philanthropy comes in many guises, but perhaps no single figure better encapsulates its delusions, pretensions and misdirections than does the lead singer of rock band U2, Paul Hewson, aka Bono.

That’s because Bono is more than a mere giver of charity – indeed, his fame in this realm has nothing to do with the spending of his own considerable fortune on the needs of the poor. He is, instead, an ‘advocate’, and as such has become a symbol of the essentially benign character of the West’s rich elite, ever ready to help the world’s poor – just waiting for a little encouragement, and a few good ideas, to eliminate hunger and poverty forever. This makes him an ideal frontman for a system of imperial exploitation and war whose depredations and depravity remain as savage as ever.

Bono’s own description of what he does for a living is ‘travelling salesman’, latest in a line:

A lot of our family are traveling salesmen. And of course that is what I have become! I am very much a traveling salesman. And that, if you really want to know, is how I see myself. I sell songs from door to door, from town to town. I sell melodies and words. And for me, in my political work, I sell ideas. In the commercial world that I’m entering into, I’m also selling ideas. So I see myself in a long line of family sales people.1

He has certainly been a more-than-competent seller of his musical work, and of himself. In his own version of the metaphor, politically he travels the world selling ideas about how to help the world’s poor – selling them mainly to the powerful people and institutions that can turn those ideas into reality. This is at best a partial account, however: in reality the idea that he is most seriously engaged in selling is the one about how those powerful people and institutions are genuinely committed to making the world a more just and equitable place. And he’s selling that to us.

Bono is nothing if not cosmopolitan. As an Americanised Irishman who has conspicuously joined forces with the British government in the past and is linked in the public eye with the fate of Africa, Bono is among the most thoroughly transatlantic of elite figures. (Former Irish attorney-general Peter Sutherland, chairman of Goldman Sachs International, ex-chairman of BP, and before that the first head of the World Trade Organization, is perhaps his nearest globe-bestriding equivalent – an adviser to banks and governments who has been called ‘the father of globalisation’2 – and we shall see that Bono’s similarities to such a thoroughly establishment character go beyond their moneyed Dublin accents.) In the United States, the belief that Bono brings some vaguely understood ‘European’ value-set to the global discussion may be part of the reason that he is viewed widely there as a largely benign and politically left-liberal figure. At one of George W. Bush’s warmest public appearances with the singer (‘Bono, I appreciate your heart’), the then-president couldn’t resist an anecdote that relied for its humour on the perception that Bono was his political opposite: ‘Dick Cheney walked in the Oval Office, he said: “Jesse Helms wants us to listen to Bono’s ideas.” ’ This brought the house down, with Bono himself smiling and clapping.3 This political perception, however, is based upon a misunderstanding of both his own ‘values’ and those of institutional Europe: neither Bono nor the EU is nearly as committed to social justice and collectivist values as US pundits are wont to insist. Meanwhile, his tendency to verbal and emotional Americanisms is part of the reason he is viewed with greater suspicion in Europe – or at least, strikingly, in Britain and Ireland, where Bono is largely a figure of ridicule and the object of often-nasty abuse. The British comic magazine Viz called him ‘the little twat with the big heart’, while writer Jane Bussmann suggested in the Guardian that Bono purveys ‘self-serving bollocks’, with Africa serving a ‘masturbatory function’ for him.4 Then there is the oft-heard, surely apocryphal story of a Glasgow U2 gig when Bono silenced the audience and began a slow hand-clap, then whispered weightily: ‘Every time I clap my hands, a child in Africa dies.’ A voice cried out from the audience: ‘Well, fucking stop doin’ it then.’5

Ridicule of this sort is widespread in Ireland but rare in the Irish media, where U2’s friends are many and their influence and patronage large. Indeed, consideration of Bono in his home country is complicated by the peculiarly Irish concept of ‘begrudgery’, an alleged national tendency to tear down those who are successful. This tendency, insofar as it exists, is born of a healthy, possibly postcolonial suspicion that the world is less meritocratic than it makes out, or that success has often come at a moral cost. Sadly, begrudgery is more often bemoaned than typified: ‘fuck the begrudgers’ is Ireland’s ancient and venerable and ubiquitous version of ‘haters gonna hate’.

Petty begrudgery certainly exists; most Dubliners have probably either said or heard the following: ‘I saw Bono in town today, but I pretended not to recognise him – I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction.’ In reality, however, Ireland was all too short of begrudgers during the 1990s and 2000s boom years known as the Celtic Tiger, when financiers, bond-holders, politicians, journalists, property developers and even rock stars were inflating a mad bubble that, when it burst, decimated economic life in the country. This book, in any case, has nothing to do with envy and doesn’t question the basis for Bono’s success – the music industry is probably slightly more

meritocratic than most – but rather how he has chosen to use it politically.

The widely varying views of Bono across and within countries pose a dilemma for the writer, especially one writing for an international audience. How seriously can you treat a figure who is so often ridiculed, in such a range of venues, for so many reasons? There’s also the fact that Bono, as a public figure, can be hard to pin down because he works in so many registers even by the standards of our frictionless, boundaryless celebrity culture: one day, it seems, you read that he is meeting the leaders of the G8, the next that he is pursuing his ex-stylist through the courts to recover a hat; this morning he’s selling you an iPod, this evening it’s his version of the Irish peace process. Ultimately, I have endeavoured to take him as seriously as he appears to take himself, which is to say ‘very’ but with regular efforts at deprecation and light relief. The reason I take seriousness as a starting point has a only a little to do with the respect that any person is due – too much of the ridicule of Bono is dumb and misguided anyway – but more to do with the fact that he appears to be taken seriously (his organisations funded, him personally invited on to prestigious platforms) by the world’s most powerful people. To understand why they do that means rising above mere terms of abuse, most of the time anyway.

I adopt this relatively high tone with some regret – as you move down the social scale the dislike of Bono gets stronger: if Tony Blair is at one, loving extreme, then the graffiti-scrawlers of inner-city Dublin are at the other, and I would hate to think of the latter feeling entirely neglected. But in a world where the New York Times mostly treats Bono like a guru, whereas many Guardian writers treat him like a fool; where countless continental Europeans regard him as a great artist, while America’s South Park satirists depict him as literally a piece of shit; where the BBC does a slightly probing TV documentary called Bono’s Millions in 2008, then devotes a whole day of promotional radio programming to the release of U2’s new album in 2009; where a friend I meet in the pub wonders why I would want to criticise Bono, then one I meet on the street reckons my task is too easy to be a proper challenge – in such a world there is no perfect way to approach this book. I hope the way I’ve chosen makes it more likely that some of Bono’s many fans and admirers will be prepared to engage with my arguments.

I am myself neither a big fan nor a dedicated detractor of U2’s music. The Frontman considers Bono largely as a political operator, rather than as a cultural producer. Bono himself many years ago said he saw the roles as separate, and music as a largely useless vehicle for political change. So this will not be the book that decides if Achtung Baby is really better than War. But, even within those limits, it would be remiss for this book not to consider, for example, what ‘Sunday Bloody Sunday’ tells us about Bono’s posturing on Irish politics, or whether U2’s turn from an American toward a European visual and musical aesthetic in the early 1990s had any political analogue. Insofar as the business, the politics and the music are intertwined, it is important to reflect that, as well as to try to unravel them.

This is, obviously, not conventional biography; nor is it an effort at psychological profiling of its subject. Although I indulge in occasional speculation about his thoughts and motives, it will not, sadly, be possible to get right behind the wrap-around shades and discern what interplay of idealism and cynicism gives rise to a figure like Bono. I am loath to judge another man’s motivation, but nor would it be appropriate simply to assume, despite what many of his acquaintances have told me, that in his political and humanitarian roles ‘he means well’. The point of The Frontman is to focus not on what motivates Bono but on his rhetoric, his actions, and their consequences. For nearly three decades as a public figure, and especially in this century, Bono has been, more often than not, amplifying elite discourses, advocating ineffective solutions, patronising the poor, and kissing the arses of the rich and powerful. He has been generating and reproducing ways of seeing the developing world, especially Africa, that are no more than a slick mix of traditional missionary and commercial colonialism, in which the poor world exists as a task for the rich world to complete. In big and small ways, he has turned his attention to a planet of savage injustice, inequality and exploitation, and it is not unreasonable to argue that he has, in some ways, helped make it worse.

Has he also helped make it better? There is no doubt that some of his campaigning and the work of the organisations he supports have improved the lives, health and well-being of many people in Africa. It would be silly to insist otherwise. And it would be presumptuous in the extreme to suggest that this or any other book can omnisciently weigh up the faults and accomplishments and deliver a definitive, objective verdict. I have endeavoured to give credit to Bono where I believe it’s due, but I don’t pretend to be a neutral arbiter. I could build and wallpaper an outhouse with the literally hundreds of books and articles that explicate How Bono Makes It Better: they are readily available online and in your local library. This one sets out to make the opposite case.

Bono himself is not shy about taking a lot of credit. He recently called his campaigning ‘a movement that changed the world’.6 In the midst of the George W. Bush years, he said: ‘People openly laughed in my face when I suggested that this administration would distribute antiretroviral drugs to Africa. They said, “You are out of your tiny mind.” There’s 200,000 Africans now who owe their lives to America.’7 The construction of those sentences makes it impossible to resist the invitation to substitute the word ‘America’ with the word ‘me’.

The idea that Bono makes it worse is, one might reasonably object, simply a political opinion – one based on what I think is clear-sighted, well informed analysis, but an opinion nonetheless. Other writers have looked at the same career, the same facts, and drawn opposite conclusions. Readers are invited to judge for themselves. However, the depoliticising language of humanitarianism, the image of Bono as outside, above and beyond politics, has often rendered the expression of mere political difference about him difficult to express. So whether or not you ultimately agree that Bono ‘makes it worse’, the point of this book is to place him and, by extension, celebrity humanitarianism firmly in the realm of politics, and therefore of political difference. To do that means to underline a few indisputable facts: that he stands for a particular set of discourses, values and material forces within a wider debate about global poverty, development and justice; that though these discourses, values and forces are often vaguely and misleadingly expressed, these can broadly be characterised as conservative, Western-centric and pro-capitalist; that they are seen as fundamentally non-threatening by the elites that have wreaked havoc on the world; and that they are capable of being vigorously contested and criticised both in principle and in terms of their effectiveness. In other words, after reading this book, you might well still believe that Bono is right, but perhaps no longer believe that his rightness is self-evident, beyond argument.

Whether or not Bono is right, I hope it will be difficult for anyone who has read this book to maintain that he is ‘left’. Indeed, since 2005 he and his organisations have been frequently derisive of approaches that they see as leftish. ‘It … would be really wrong beating a sort of left-wing drum, taking the usual bleeding-heart-liberal line’ is a typical Bono statement about where he locates his campaigning politics.8 Of course he would also say, in the unlikely event that he were asked, that he is not right-wing either. It is precisely the notion that the technocratic ‘problem-solving’ approaches that he advocates are somehow apolitical that needs to be contested.

The rise of Bono as a political operator since the late 1990s is tied to larger and disquieting developments in transnational governance, by which the biggest states, corporations, foundations and multilateral institutions have undermined democratic accountability and sovereignty throughout the world, often in the name of humanitarianism. Bono is a relatively small (though nonetheless significant) player in this project, and to consider it fully is beyond the bound

s of this volume. By the end of the book, as Bono’s close ties to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and its agenda for African development are considered, readers may be encouraged to learn more.

Before you get to that point, The Frontman is divided into three thematic strands that are drawn in part from the chronology and geography of Bono’s own story. Chapter 1, ‘Ireland’, looks, among other things, at the myths and realities of Bono’s origins in Dublin; the way he and U2 related to the Irish Troubles; their emergence as symbols of Irish confidence and regeneration, and then as major players in domestic business and property investment, before and after the collapse of the Irish economy. Chapter 2, ‘Africa’, examines how Africa has been constructed in Bono’s work and how he came to steal the show at Live Aid in 1985, eventually overtaking its progenitor Bob Geldof as the main ‘African’ advocate in Western politics and show business, pushing neoliberal solutions to the continent’s problems. Chapter 3, ‘The World’, looks at Bono’s multinational business interests and his role in events such as G8 summits, cosying up to the likes of Jesse Helms and Paul O’Neill, whitewashing war criminals of the Iraq invasion such as Tony Blair and Paul Wolfowitz, and acting as a sidekick to shock-doctrine economist Jeffrey Sachs. Some important but non-political aspects of his career are absent entirely; some of the most important political events and issues are dealt with in two or even three of the chapters, examined each time from a slightly different perspective.

The great genius and the great danger of Bono is that – not unlike that ‘community organiser’ Barack Obama – he does a plausible imitation of an activist. His discourse rings with familiar cries for justice, and some of us who should know better hear our yearnings in his voice: he is, after all, an accomplished singer. British journalist George Monbiot wrote after the 2005 G8 summit, in which Bono played such a clever and shameful role:

The G8 leaders and the business interests their summit promotes can absorb our demands for aid, debt relief, even slightly fairer terms of trade, and lose nothing. They can wear our colours, speak our language, claim to support our aims, and discover in our agitation not new constraints, but new opportunities for manufacturing consent. Justice, this consensus says, can be achieved without confronting power.9

The Frontman

The Frontman