- Home

- Harry Browne

The Frontman Page 2

The Frontman Read online

Page 2

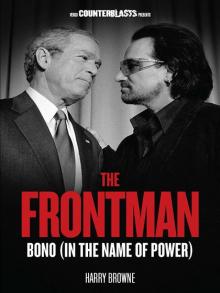

Bono comes in the name of that power, assuring us that if we make our peace with it – ‘campaigning’, sure, but only within its terms – it will make everything all right. That power, true to its pretensions as an equal-opportunity employer, is happy to employ a talkative Irish rock star in designer sunglasses and leather trousers to deliver the message, if that’s what it takes.

It’s nothing personal, Bono, but I’m afraid one of the first steps for people seeking real justice is that we stop buying the message you’re selling.

1 IRELAND

‘WHAT A THRILL FOR FOUR IRISH BOYS FROM THE NORTHSIDE OF DUBLIN …’: ORIGINS

Bono is rich: he wears designer clothes, flies around in private jets, drives any one of five luxury cars, loves the finest of food and wine – his net worth has been estimated at more than a half-billion dollars.

Bono is famous: he fronts the most consistently popular band of the last three decades, has millions of fans, sings several of our era’s best-known songs – he wears sunglasses that draw attention to him rather than deflect it.

Bono is powerful: his counsel is sought, heard and heeded at the very highest levels of national and international governance – he is, as the Ramones might say, friends with the president, friends with the pope.

But Bono wants you to know he hasn’t forgotten where he comes from. As thousands gathered on Washington’s Mall in January 2009, and millions watched on TV, he told the man who would be inaugurated as US president two days later: ‘What a thrill for four Irish boys from the northside of Dublin to honour you, sir.’

When Bono, preening for Barack Obama and the wider world outside the Lincoln Memorial, chose these words of pseudo-self-deprecation to capture the all-round awesomeness of U2’s presence, he was indulging in a mashup of signifiers, typical of those who carefully craft their own images. At its most basic level, the ‘What a thrill for …’ was just an adaptation of American Dream boilerplate, which was flowing especially thick in those Obama-worshipping days: ‘We were just four Irish boys’, was what he meant, ‘and now look at us.’ ‘Irish’, though, doesn’t necessarily signify a foreign nationality for many people in the US, so much as a certain kind of Americans, or even just a bout of bad temper. However, Bono did throw in a few extra words of geographic specificity – ‘from the northside of Dublin’ – and in context one got the impression it was the realm of the working class, the baddest part of town. And it probably doesn’t hurt that ‘north’ and ‘Irish’ may also conjure up memories of old TV news footage of bombs and barbed wire. Suddenly, Bono, Adam, Larry and The Edge are cast in the mind’s eye as street urchins who dodged the crossfire of the Irish Troubles and lived to sing about it. Hey, didn’t they call two of their first three albums Boy and War?

This discussion of origin-mythmaking is not simply meant to suggest that Bono and his band are somehow inauthentic (though it is true that the concept of ‘authenticity’ and its discontents have stalked U2’s career). Nor is it meant to provoke the arguably racist questioning of ‘how Irish are they really?’ beloved of some hostile commentators, who point out that ‘Paul David Hewson’ bears no trace of Gaelic origins – but the same can be said about the names of millions of people who are unquestionably of Irish origin.

It is meant to disentangle the facts of Bono’s life from his rhetoric. In Dublin, the often-capitalised Northside and Southside are states of mind as much as states of geography, and are class signifiers to such an extent that, for example, the working-class Liberties south of the river Liffey are often described as ‘not really Southside’; similarly, the seaside urban villages of Clontarf, where Bono and the boys met at Mount Temple Comprehensive School, and Malahide, where Adam and The Edge lived as kids, are posh enough to be rhetorically exempted from the Northside that abuts them.

To be fair, we have no idea whether the word ‘northside’ carried a capital N in Bono’s mind’s eye when he drawled it outside the Lincoln Memorial. However, there’s no doubt that’s the way it was heard in Ireland: the Irish Times, quintessential Southside newspaper, devoted a column after the Obama affair to the trashing of Bono’s claim to real Northside-icity. (It is one of the small ironies of Dublin’s division that it is generally Southsiders who are most protective of the Northside and Real-Dub – ‘real Dublin’ – brands, treating them like Appellations Controlées, the guarantees of regional authenticity on bottles of French wine, denouncing any suspiciously middle-class figures, of whatever geographic origin, who attempt to wear the labels as badges of street-credibility.) Bono, it seems, with his unDubby mid-Atlantic accent and his mansion overlooking the most-definitely-Southside Killiney Bay, is forever to be condemned for alluding significantly to the fact that he grew up, genuinely, on the northside of Dublin city.

That Irish Times columnist remarked: ‘It’s not as if most of Bono’s friends are either dead or in jail. Last time I looked, they were making soundtracks and bowls.’1 This rather strangely and cleverly inverted put-down perhaps says more than it intends to about how the Irish Times sees the essence of Northsidedness – ‘dead or in jail’, like something out of a rapper’s boast about his unlikely rise from the streets. But it also helps us to get a handle on how misleading, or at least inadequate, Bono was being when he summarised U2 as ‘four Irish boys from the northside of Dublin’, a description that in the circumstances certainly signified (to listeners and viewers of whatever sensitivity) origins distant and isolated from centres and moments of cultural power like the one he was enjoying on Washington’s Mall, whether or not it signified full-blown poverty and deprivation.

The reality is that Bono grew up in a middle-class (that term is more upmarket in Ireland and Britain than in the US) and slightly countercultural enclave of the poor and working-class north Dublin area called ‘Ballymun’ (another signifying Appellation Controlée that he is occasionally abused for employing). ‘Violence … is the thing I remember most from my teenage years’, he has said, but without giving any more detail than a suggestion that, when he and his pals strayed into working-class territory, it was, you know, kind of scary.2 Ballymun’s notorious, now-demolished tower blocks may have been evoked in Bono’s ‘Running to Stand Still’, but he grew up a safe distance away on Cedarwood Road, full of comfy semi-detached homes with nice gardens, lawns and driveways.

In the early 1990s Bono tried to convince an American journalist, Bill Flanagan, that as a child he used to hustle tourists in (Protestant) St Patrick’s Cathedral:

‘I would charge them for tours of the cathedral’, [Bono] says. ‘I made good money.’

‘Oh’, I say, ‘you were an urchin.’

‘I was!’ Bono says brightly, at which [Bono’s wife] Ali bursts out laughing. She knows her husband never urched.3

Bono was no child of the streets; nor were the city and country he inhabited the complete backwaters that they look like in so much retrospection. Born in 1960, Bono was raised in a Republic of Ireland that was economically and culturally emerging from the isolation of the first four decades after independence. Emigration had slowed very dramatically, and with a new economic strategy of seeking foreign investment, the country was even attracting families from Britain like those of Bono’s future bandmates: Edge’s dad was an engineer, Clayton’s a pilot – higher earners than Bono’s father, with his white-collar job in the postal service. The sometimes-maddening tendency of the Irish economy to be out of sync with its neighbours was occasionally a good thing: for example, while Britain went slouching toward the Winter of Discontent in the late 1970s, Ireland, including the boys of U2, enjoyed a mini-boom.

New political winds were blowing through the era too: a leading politician could credibly claim that ‘the Seventies will be socialist’; there was a vigorous women’s liberation movement that got a good airing in broadcast and printed media; and there was of course a civil rights movement and ‘armed struggle’ across the border in British-controlled Northern Ireland. By the time Bono was starting secondary school at the new, li

beral, Protestant-run, multi-denominational, co-educational Mount Temple, one of Britain’s favourite blues guitarists was Cork-based Rory Gallagher, and within another year or two Thin Lizzy – with a black Dubliner, Phil Lynnott, as frontman – were blasting up the rock charts on both sides of the Atlantic. And that’s to say nothing of the centrality of Irish music and musicians in the ongoing international ‘revival’ of traditional and folk music. Ireland wasn’t rich, but it was a reasonably cool place to be from, and in, with nothing much cooler and more connected than to be a teenage rock ’n’ roller at Mount Temple, with its largely well-off student body. When 1977 came along, some of the punk bands made it to Dublin on tour.

You might call them cosmopolitan provincials, or provincial cosmopolitans; either way, middle-class young people in Dublin in the 1970s were capable of being clued-in about the wider world, and even feeling that they could exert some influence over it. Pirate radio and a TV aerial that could pick up the BBC meant that you needn’t miss a thing. In 1977 Niall Stokes launched an ambitious and specifically Irish title, Hot Press, an irreverently liberal music magazine, which quickly turned into a must-read for local fans and bands alike, especially in Dublin.

Ah, but there was, of course, the power of the Catholic church to spoil all that, and for many people it was a terrible scourge on their lives. Its role shouldn’t, however, be exaggerated, as it often is in the memories and polemics of those who get over-excited about Ireland’s eventual liberation from its yoke. While it was true that the Catholic hierarchy cast a long shadow, including over national legislation on matters such as divorce and birth control – U2 would eventually play their first benefit gig in 1978 for the Contraception Action Campaign4 – it didn’t especially darken places like Mount Temple.

Bono has made much of his parents’ religiously mixed marriage: ‘My mother was a Protestant, my father was a Catholic; no big deal anywhere else in the world but here’ – benighted Ireland, the only place in the world where denominational differences matter. Except that Bono has never shown that his parents’ mixed marriage was anything like a ‘big deal’ in the circles he inhabited. Indeed, it is striking that in an Ireland where the Catholic church’s Ne temere doctrine of 1908, ruling that children in mixed marriages must be raised Catholic, had been declared by the Supreme Court in 1950 to be enforceable in law, Bobby and Iris Hewson felt free to make their own arrangements: they agreed to raise their children alternately, the first Protestant, the second (Paul, later to become Bono) Catholic – or, by another telling, boys Catholic and girls Protestant – and then didn’t stick to that arrangement in practice, with Bobby leaving their two boys in their mother’s (Protestant) spiritual care. Young Paul went to mainstream Protestant primary schools.5

The Hewsons’ mixed marriage, and whatever agonies they may have suffered because of it, is of course a private matter; it may well have been harder than we’ll ever know. No one would dream of questioning the real trauma and loss that accompanied Iris Hewson’s death when young Paul was fourteen. But it is difficult not to suspect that Bono locates himself as a childhood victim of sectarian pressures at least partly to associate his origins with the conflict in Northern Ireland, understood in much of the rest of the world to be a sectarian Protestant-versus-Catholic war. Bono’s repeated insistence that he had a little piece of the war in his very own childhood home – he had, he said in a Washington speech in 2006, ‘a father who was Protestant and a mother who was Catholic in a country where the line between the two was, quite literally, often a battle line’6 – is part of the backdrop to his decades of posturing on that conflict. (Strangely enough, in that speech he reversed his parents’ actual religious affiliations.) In reality the Troubles took place almost in their entirety sixty-plus miles up the road in Northern Ireland; and when the conflict made rare, bloody intrusions into the Republic, it didn’t discriminate between Protestant, Catholic and ‘mixed’ victims.

The four boys in U2, meanwhile, were not very different from most of the people who would become their fans across Europe and North America: comfortably off, liberally raised, and drawn inexorably to the international language of rock ’n’ roll. Somewhat more unusually for teenagers at that time and in those circumstances, Bono and his mates were attracted by another global language: that of Christianity.

DANDELION MARKET: U2 EMERGES

In many ways, their enthusiasm for Jesus was more outré and cutting-edge than their musical aesthetic. Under their first two names of Feedback and The Hype, the band that would become U2 played covers of songs by middle-of-the-road chart acts such as Peter Frampton, the Eagles and the Moody Blues well into 1977 – many months after the Sex Pistols had released ‘Anarchy in the UK’ and the older fellas in Dublin band the Boomtown Rats had headed off to join the punk scene in London. When young Bono wrote his first song, ‘What’s Going On?’, he apparently didn’t realise that Marvin Gaye had got to the title first. Only after the Clash came to town in October 1977 did the band begin to punk up their sound and their look, and finally their name.7

Paul Hewson grabbed his own stage-name not from any Christian commitment to doing good but from a prominent hearing-aid shop in central Dublin that advertised ‘Bono Vox’ (good voice) devices. (The name is pronounced, as one of his detractors notes, to rhyme with ‘con-oh’ rather than ‘oh-no’.8) His youthful religious explorations began at an early age, when he befriended neighbour Derek Rowan (later to become ‘Guggi’, a successful painter), who belonged to an evangelical Protestant sect that had been founded in Dublin in the 1820s, the Plymouth Brethren.9 The intensification of his religious curiosity, at home and in school, has been attributed to the loss of his mother when he was fourteen; when Larry Mullen’s mother died a few years later, the two teenagers delved together into Bible study. Religious observance was high in Ireland, among both Protestants and Catholics; religious identity was important to a substantial portion of the population; but religious enthusiasm was and is seen as a distinctly odd phenomenon in the Republic. Back in the 1980s many Irish observers would wrinkle their noses in suspicion and tell you that U2 were ‘some kind of born-agains’ – the phrase suggesting an Americanised Protestant evangelicalism. Or, on the other hand, they would raise eyebrows and explain that U2 ‘had gone charismatic’ – a term which, unlike ‘born-again’, pointed to the possibility of a basically Catholic orientation, but one far removed from the quietly muttered rituals that dominated most Irish-Catholic practice.

Ireland is a country where you can still be half-seriously asked if you’re ‘a Catholic atheist or a Protestant atheist’, but most Irish people seem to have lost interest long ago in whether Bono and two of his bandmates (bassist Adam Clayton stayed out of the Bible scene) were or are Protestant Christians or Catholic Christians – though the interest in scripture points to the former. The prayer group they joined in 1978, and eventually left more than three years later when they came under pressure from fellow members to abandon rock ’n’ roll and its trappings, was called Shalom; but, despite the name, Shalom’s members were not Jewish Christians, and, just to add to the confusion, the organisation has been described as both ‘evangelical’ and ‘charismatic’, with ‘Pentecostal’ thrown in for good measure.10 Bono’s wedding in 1982 was conducted in the conventionally Protestant Church of Ireland – part of the Anglican communion – to which his wife Ali Stewart belonged, but with some of his friends’ Plymouth Brethren colouring thrown in.11

Whatever words you use to describe the band’s early Christianity, it doesn’t appear to have made much of a mark on the Dublin music scene. In February 1979 Bono told Hot Press writer Bill Graham about the religious commitments of his circle of friends in the earnest, creative, post-hippy imagined community they called Lypton Village, ‘One thing you should know about the Village: we’re all Christians.’ Graham, however, chose to leave that revelation out of his published interview with the band he was already growing to love, in order to protect their reputation.12 Oddly enough, U2 were apparent

ly stalked for a few weeks in 1979 by a group of young toughs from Bono’s neighbourhood styling themselves the ‘Black Catholics’, who denounced U2 as ‘Protestant bastards’. But this seemingly had more to do with class than religion – ‘Protestant’ translated in this case as ‘posh and stuck-up’; and after a couple of tussles the harassment was ended by Bono marching down Cedarwood Road to confront the daddy of one of his persecutors.13 The Christians of U2 weren’t, in any case, persecuted for their religious beliefs; nor did they make much of proselytising them.

But even as U2 were embracing God they came face to face with Mammon, in the form of Paul McGuinness. Bono has described U2 as ‘a gang of four, but a corporation of five’,14 with the fifth and equal partner being the hard-headed capitalist who has managed the band from nearly their start. McGuinness, a decade older than the band, was and is a traditional Irish Catholic, which is to say a man without a shred of obvious, let alone ostentatious, Christianity. (He famously shot down the band when they were hesitating over a set of gigs, under pressure from Shalom comrades: ‘If God had something to say about this tour he should have raised his hand a little earlier.’15) From the time he took on management of the band after passionate encouragement from Graham of Hot Press, McGuinness served the purpose of deflecting and absorbing criticism: he could be a tough, obsessive bastard so they didn’t have to. He aroused far more resentment among other musicians than anything involving U2’s religion ever did. One false rumour doing the rounds in 1979 suggested that McGuinness made a phone call pretending to be a London A&R man in order to get U2 a gig opening for the popular English New Waver Joe Jackson, insisting that local rivals Rocky De Valera & the Gravediggers had to be dumped so he could see U2. (That change was never in fact made.) When Heat magazine printed the untrue rumour, McGuinness initiated a lawsuit that soon shut the magazine down.16 McGuinness was a man who was tough enough to attract conspiracy theories, and dealt firmly with adversity.

The Frontman

The Frontman